We have covered How Many Steps Should I Get? as it relates to health and weight loss maintenance previously.

But, do higher step counts blunt hypertrophy? This claim has been made on the internet and this post is all about attempting to understand if this assertion is valid and what evidence exists directly and tangentially to this topic. The interference effect of endurance training on strength and hypertrophy is very likely overstated. Petre and colleagues found that concurrent training negatively affected strength gains in trained individuals, but only when the resistance and endurance training were performed in the same session [1]. Whereas, untrained and moderately trained subjects' strength gains seemed to be unaffected by concurrent training regardless of whether it was performed in the same session. Schumann and colleagues found a negative effect of concurrent training on explosive strength, but no statistically significant impact on strength or hypertrophy [2].

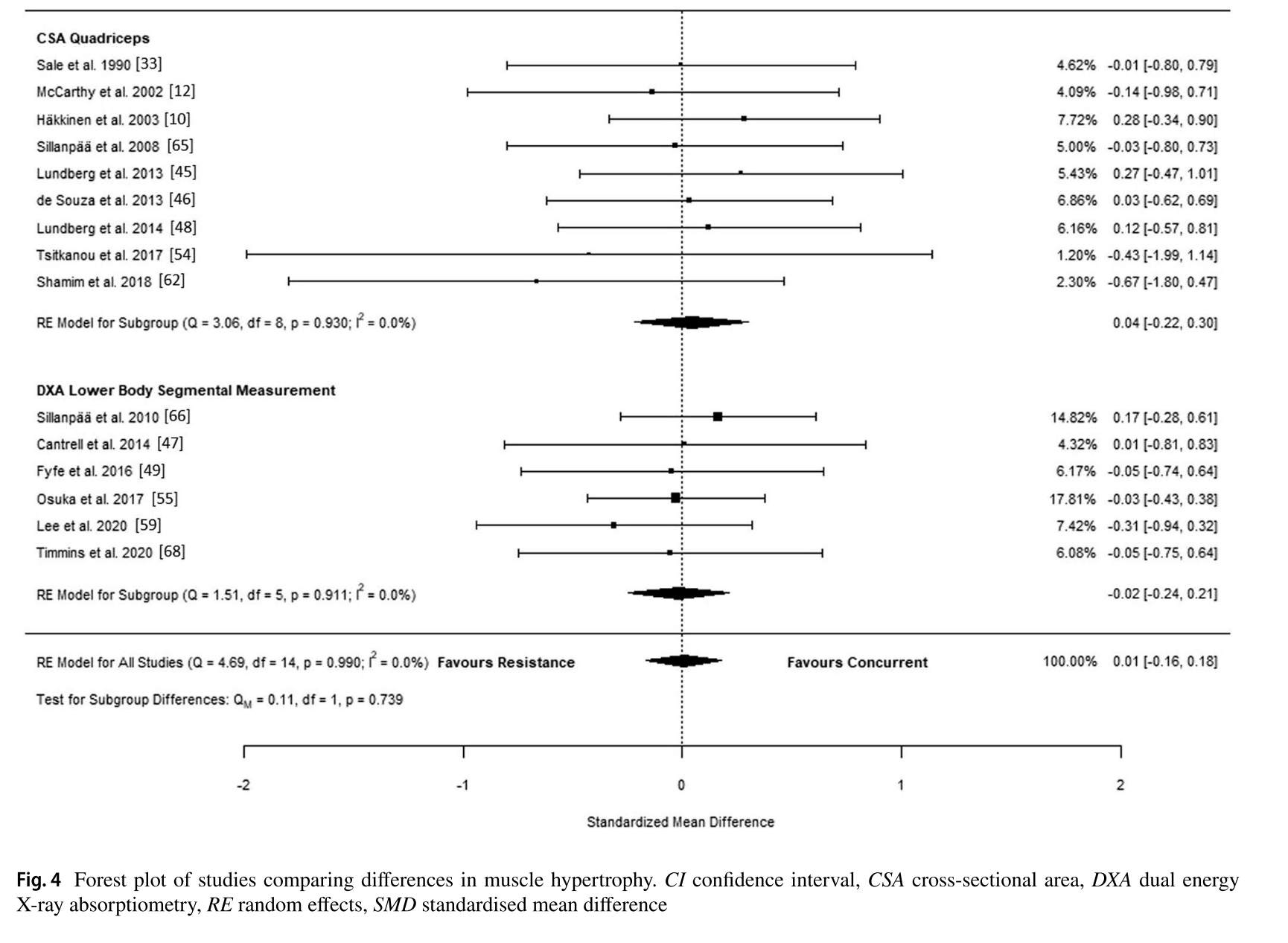

“The main finding was that concurrent aerobic and strength training did not interfere with the development of maximal strength and muscle hypertrophy compared with strength training alone. However, the development of explosive strength was negatively affected by concurrent training. Our subgroup analysis showed that this negative effect was exacerbated when concurrent training was performed within the same session, compared with when aerobic and strength training were separated by at least 3 h. No significant effects were found for other moderators, such as type of aerobic training (cycling vs. running), frequency of concurrent training (> 5 vs. < 5 weekly sessions), training status (untrained vs. active), and mean age (< 40 vs. > 40 years).” -Schumann et al., 2022

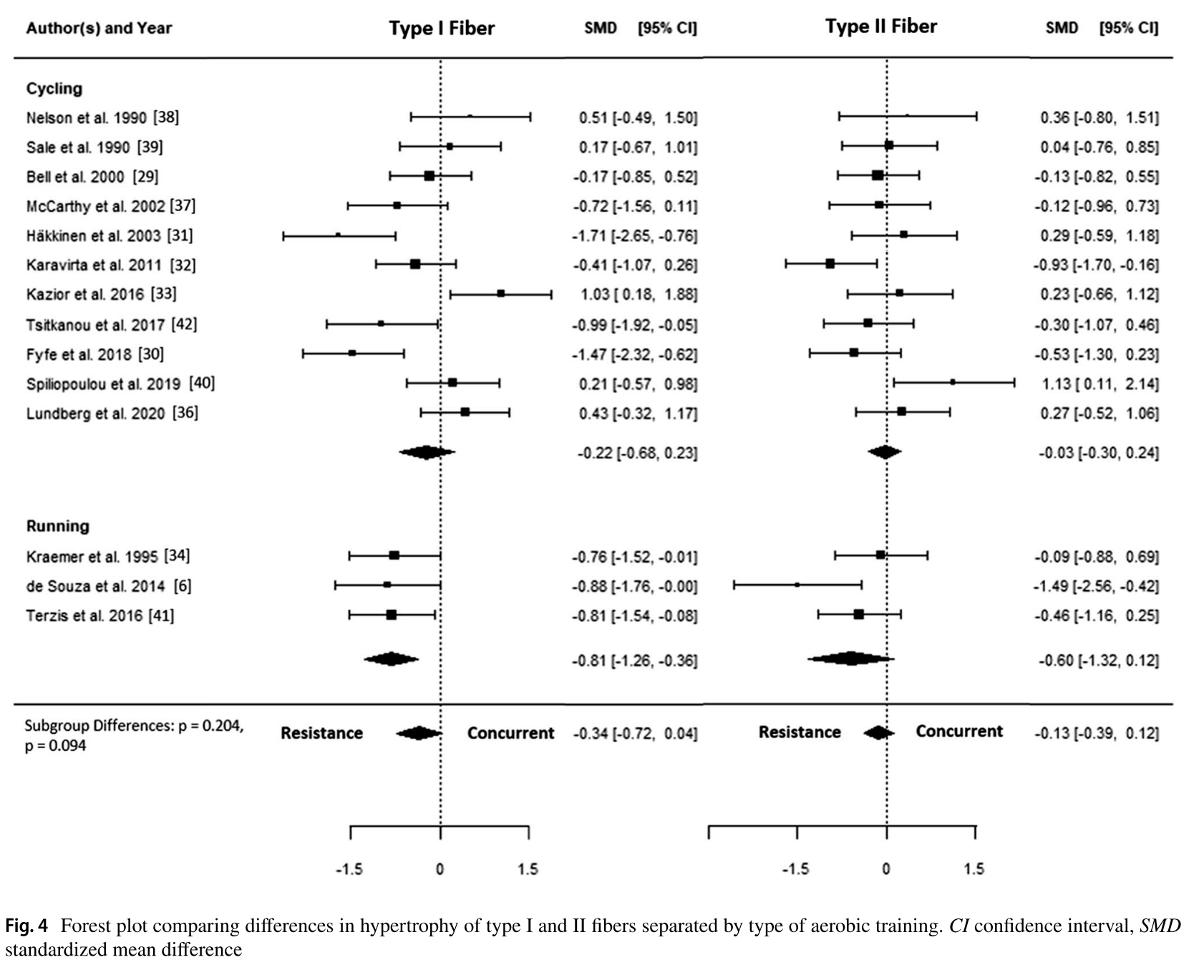

The same research group then performed another meta-analysis on the effect of concurrent training on muscle fiber hypertrophy [3]. They found that concurrent training resulted in a small effect size decrease in the hypertrophy Type 1 muscle fibers. This finding was only significant in studies that involved running and not cycling. Additionally, Kang and colleagues did not find that concurrent HIIT-based endurance programs negatively influenced strength or lower body power in team sports athletes [4].

That feels like enough slapping down of meta-analyses that are only tangentially related to the question at hand. The studies that are included in these meta-analyses are at far higher intensities than walking so let’s dig into the direct research we have on higher step counts and hypertrophy.

To date, I am not aware of a study that compared the results of the same resistance training program under conditions of graded step count exposure in untrained or resistance-trained subjects. Pubmed search queries containing steps, resistance training, and hypertrophy returned zero results. Walk, resistance training, and hypertrophy returned 43 results, but included only one directly relevant study in 12 untrained older women which found that moderately intense walking did not negatively affect muscle hypertrophy from a bodyweight exercise circuit [5]. Running down the citations from this study, a large cohort study found that bone mass and skeletal muscle mass were preserved or increased in subjects who walked five days per week for at least thirty minutes and performed resistance training two days per week [6]. A search for non-exercise physical activity, resistance training, and hypertrophy returned 13 studies, but none were relevant. Thus, this niche area appears to lack more direct research, and to try to answer this question I will have to look for hypertrophy studies where the researchers tracked step counts.

Longland et al., 2016 drove untrained overweight male subjects into the absolute ground with six times a week concurrent training combined with an estimated 40% energy deficit and found that under high protein conditions, these subjects still gained 2.6 lb of lean body mass while losing 10.5 lb of fat in four weeks [7]. Additionally, these subjects maintained an average step count of 11,915 ± 2492 steps per day throughout the intervention. This is one of the more remarkable findings in the S&C world and we have discussed it in more detail HERE. In this population, it does not appear that ~12,000 steps per day and concurrent training hindered hypertrophic gains.

Getting even more out there, Soriano and colleagues found that 12,881 steps per day did not seem to hinder strength gains from twenty-four sixty-minute resistance training sessions over twelve weeks in female breast cancer survivors, although there was not a direct comparison group who was less active[8].

That’s all I could directly find on resistance training studies that also tracked step counts (if you know of any additional studies please send them my way). The next step I thought of was to compare the volume of running in the studies from the above metas that found a negative impact on hypertrophy to see how this could feasibly relate to step counts.

It appears that no study that was included in the Schumann et al. meta found a statistically significant effect of aerobic training on hypertrophy [2].

If we look at the three negative running studies from the meta published by Lundberg and colleagues [3] we see that two of these studies included high-intensity running in the same session which is not very applicable to our current question [9, 10] and subjects in the other study by Terzis and colleagues performed 30 minutes of running at 60-70% of their max heart rate immediately after lower-body power-sessions [11].

This study by Terzis and colleagues found that after six weeks this duration and intensity of running performed immediately after power training impaired increases in vertical jump height, peak power, and muscle fiber hypertrophy [11]. A highly trained runner might be able to hold an 8-minute mile at this heart rate, someone who is less trained will be significantly slower so perhaps we could say it is best not to run 2 to 3.5 miles immediately after a lower body resistance training.

This distance would roughly equate to 5 to 8,000 steps. Thus, if one was extremely risk averse to losing gains in strength and hypertrophy it might be best to not go for a long walk immediately after a lower body training session. I am not ready to say with any type of certainty that a light 10 to 20-minute cool-down walk after lower body training would negatively affect one's gains. Given the findings of this same meta and others, I am more confident that I don't think a hike later in the day or on a subsequent day would significantly blunt training adaptations.

TL;DR – To my knowledge, we don’t have any direct studies comparing the combination of different step counts and resistance training on muscle hypertrophy. If someone is prioritizing hypertrophy and strength gains running immediately after a lower body training seems like a poor choice and cycling is likely a better option if one has the desire to build out their program in this manner. This negative effect could be there for an activity like hiking too, but we don’t have any studies directly testing this hypothesis in trained individuals under any type of nutritional condition (i.e. a deficit, maintenance, or surplus). Given the current evidence, it is hard to justify any position that seeks to limit step counts in untrained individuals as hypertrophy and strength generally appear to be unaffected at 12,000 steps per day even with concurrent training. There is also the counter-argument which we have covered previously that different types of active recovery like walking or cycling performed outside of training may improve recovery, glycemic control, and nutrient utilization/partitioning (HERE). If increased step counts drove someone into a caloric deficit this may potentially blunt muscle hypertrophy in highly trained individuals, but to my knowledge we don't have any studies testing this specific hypothesis.

REFERENCES

1. Petre, H., et al., Development of Maximal Dynamic Strength During Concurrent Resistance and Endurance Training in Untrained, Moderately Trained, and Trained Individuals: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Sports Med, 2021. 51(5): p. 991-1010.

2. Schumann, M., et al., Compatibility of Concurrent Aerobic and Strength Training for Skeletal Muscle Size and Function: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med, 2022. 52(3): p. 601-612.

3. Lundberg, T.R., et al., The Effects of Concurrent Aerobic and Strength Training on Muscle Fiber Hypertrophy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med, 2022. 52(10): p. 2391-2403.

4. Kang, J., et al., Effects of Concurrent Strength and HIIT-Based Endurance Training on Physical Fitness in Trained Team Sports Players: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2022. 19(22).

5. Ozaki, H., et al., Combination of body mass-based resistance training and high-intensity walking can improve both muscle size and V O(2) peak in untrained older women. Geriatr Gerontol Int, 2017. 17(5): p. 779-784.

6. Lee, S., et al., Daily Walking Accompanied with Intermittent Resistance Exercise Prevents Osteosarcopenia: A Large Cohort Study. J Bone Metab, 2022. 29(4): p. 255-263.

7. Longland, T.M., et al., Higher compared with lower dietary protein during an energy deficit combined with intense exercise promotes greater lean mass gain and fat mass loss: a randomized trial. Am J Clin Nutr, 2016. 103(3): p. 738-46.

8. Soriano-Maldonado, A., et al., Effects of a 12-week supervised resistance training program, combined with home-based physical activity, on physical fitness and quality of life in female breast cancer survivors: the EFICAN randomized controlled trial. J Cancer Surviv, 2023. 17(5): p. 1371-1385.

9. Kraemer, W.J., et al., Compatibility of high-intensity strength and endurance training on hormonal and skeletal muscle adaptations. J Appl Physiol (1985), 1995. 78(3): p. 976-89.

10. de Souza, E.O., et al., Effects of concurrent strength and endurance training on genes related to myostatin signaling pathway and muscle fiber responses. J Strength Cond Res, 2014. 28(11): p. 3215-23.

11. Terzis, G., et al., Early phase interference between low-intensity running and power training in moderately trained females. Eur J Appl Physiol, 2016. 116(5): p. 1063-73.

Related Content

How Much Does Androgen Receptor Sensitivity Matter?

Nov 16, 2025

Is Training To Failure Worse Than Worthless?

Sep 19, 2025

Is Ultrasound Ready To Go Mainstream?

Jul 07, 2025